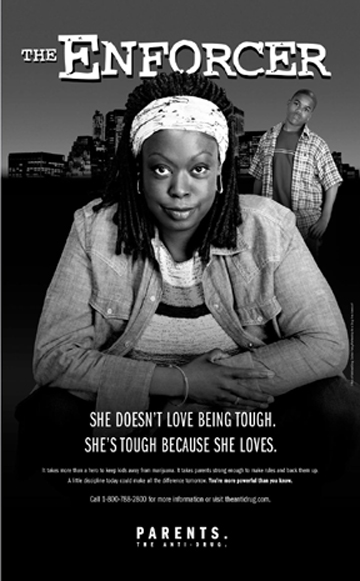

On Sunday, September 15, the poster to the right occupied a full page in the New York Times. It was produced by the National Center for Drug Policy, an agency of the federal government. The Sunday edition of that paper has a circulation of 1.7 million. I invite readers to take a careful look at the poster. Click on the link at the bottom to bring up the small print. Please read it all.

To read the poster's fine print, click larger image. The Enforcer, with her get-tough message, brings to mind comedian Bill Cosby's classic routine containing a black mother's warning to her child, "I brought you into this world and I can take you out." Cosby's audiences love it. They don't hear a terrorist threat. They hear Mom, and they love her.

Look at the young man in the photo. He appears to be in his middle to late teens, nearly full grown. Surely, any mother who hasn't learned to communicate with a child this age except by shouting and smacking isn't going to benefit from a poster. She needs serious one-on-one counseling, not specious tough-love clichés. Notice in small print: "You're more powerful than you know." Clearly, the NCDP people are cheering her on to use the tools of habit -- the very tools that have put her and her son in their present stand off. "Come on, you can do it," they seem to be telling her. "Don't be afraid. Show him who's boss. Remind him who brought him into this world."

Consider the caption under photo: SHE DOESN'T LOVE BEING TOUGH. SHE'S TOUGH BECAUSE SHE LOVES. The writers must have congratulated themselves upon producing a catch phrase that measures up to the likes of "This hurts me more than it hurts you," "I'm doing this for your own good," "Some day you'll thank me."

See the small print: "A little discipline today could make all the difference tomorrow." Indeed it can. The two stories that follow support that claim, but not as intended by the makers of The Enforcer.

A young black man told this story which I paraphrase from memory:

My father always used a stick ever since I can remember. All us kids got it. Well, the last time it happened to me I was in high school. He said he was going to teach me a good lesson. He got this broom handle, ya see, and started on me. Finally... I don't know... I guess I just snapped and went after him. You see, I was on the school wrestling team an' pretty big by then with all the training and stuff.That father is now a paraplegic. The young man was in his early twenties when I met him, and was participating in the pre-release program at California State Prison Solano where he was an inmate. I was conducting a parenting workshop with his group. He told me that he and his father have reconciled.This took place at California State Prison Folsom about two weeks before this writing. A black convict, probably in his middle fifties, sat through all the discussion without participating. He took in everything but said nothing. The session was winding to a close when the man suddenly opened up, or, to put it more precisely, let loose. His intensity filled the room. The usual chatter between the men ceased. Everyone listened as he described the time when he was a boy in Arkansas in the principal's office waiting to be paddled. He said that when the principal brought out the paddle, he asked him, "You gonna hit me with that?" The principal answered, "Yes I am, boy." He said he then bolted from the principal's office and ran home. When he told his mother what had happened, she thrashed him. That evening, when his dad came home and learned what had happened, he caught another, worse thrashing. At that point in his narrative, he looked directly at me. There was a strange blend of sadness and fury in his deep-set eyes. "You's 1,000 percent right, Mr. Riak," he said."The beatin' don't do no good. We was one beatin' family and it don't do no good. I know. Gets you messed up real good an' that's all. Look at me. Look where I'm sitting now. And my brother... every day when he was growing up, he got whupped 'til finally he run away. He's in Oregon now sittin' in the state prison. And his boys, my two nephews... Yes, they too got whupped plenty. And they is doin' time. Yes sir, Mr. Riak, we was one whuppin' and beatin' family, an look where it got us. All the men is doin' time." When he finished, I asked the class if they had been listening closely. "If you heard this man's story," I told them, "then there's nothing more I need to tell you. You have the whole picture. You know everything anybody needs to know about spanking."

I then asked for a show of hands by all who believed school paddling contributed to the early end to their formal education. Nearly half indicated it had. (When I've asked that question of previous groups, the responses were similar.) One inmate commented that in the process of getting paddled he took the paddle from the principal and hit him with it. Another said he ran away, only to be brought back to the school by the police to receive his paddling.

As the men filed out, I took the man from Arkansas aside and asked if we could meet when he was out so I could interview him about his childhood and get it on tape or perhaps video. He agreed and gave me contact information. But I doubt if we'll match what happened spontaneously in that classroom.

What shall we do about the poster?

I suggest readers call the toll-free number given on the poster (1-800-788-2800). The operator you reach will transfer you to the message center where you can tell the people at the National Center for Drug Policy what you think of their poster. Let them know that it is a dangerous, ill-advised, wrong-headed message that pretends to strengthen the family but in fact rends it apart by encouraging and justifying child abuse. It offers nothing of value to American parents, many of whom desperately need serious advice and guidance. Let them know that the hostile, authoritarian, bullying parenting style they are promoting further alienates teenagers and drives them into the street in search of escape routes where the worst dangers lie. Let them know that their poster's unintended consequence will be the very opposite of what they claim they want to achieve -- more addiction, not less; more school drop out, not higher test scores; more families in shambles, not stronger ones. Check the Web page at www.mediacampaign.org/mg/print/ad_enforcer.html to see if The Enforcer is still there, and keep calling until they take it down.

See Beating in child-rearing actually has its psychological roots in slavery,, By William H. Grier, M.D. and Price M. Cobbs, M.D., From Black Rage (1968).See Old-fashioned 'whupping' gets backing, By Christopher Quinn, (Cleveland) Plain Dealer, February 15, 1999.