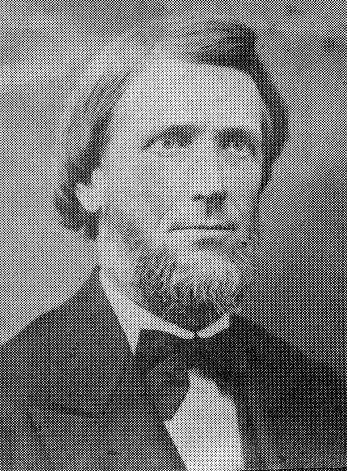

SAMUEL P. BATES |

Tribune reporter Mary Spicer's recent provocative article "Should schools spare the rod?" re-sparked debate on a question that has tormented educators ever since Pennsylvania's "free school" law of 1834. Times have changed, but the issue persists.

A Pennsylvanian who examined corporal punishment 150 years ago was Samuel P. Bates of Meadville. Best remembered as a historian who wrote highly acclaimed books on the Civil War, Bates was also a nationally noted educator. Born in Massachusetts, he came here to teach languages after graduating in 1851 from Brown University. Later he went from being county superintendent to that of general deputy superintendent of schools in the commonwealth. In this latter capacity, he inspected county schools, their curricula and staffs. Generally, he found deplorable conditions. Facilities were inadequate, teachers were poorly trained and paid, and school boards were generally opposed to raising taxes to attack the deficiencies.

It was tough being a Harrisburg watchdog. Many citizens resented the state meddling in local affairs. They had opposed the '34 law and had helped defeat for re-election Gov. George Wolfe, a strong supporter of the law.

Everywhere Bates went, his message was clear: EducatIon had to be liberal, open to every child and publicly financed. He was a progressive ahead of his time. In addition to hiring qualified teachers, he urged that school districts proyide physical training, better texts and programs for the handicapped. He also encouraged both teachers' institutes and normal schools (colleges) for the preparation of teachers. His recommended reforms were published in the Pennsylvania School Journal and The American Journal of Education and eventually were adopted.

Classroom discipline was one troubling issue Bates foresaw as a clog in the learning process. Corporal punishment was repugnant to him. He realized that he represented a minority view, but he failed to see how paddling or even threatening a child physically made that child a more responsive student.

Throughout the commonwealth he saw teachers apply the rod freely, often too freely. Spanking a child before the class created disorder in the one-room school and terrified the other children. Regrettably, he also noted that teachers were often hired simply to enforce order. Their abiIity to handle bullies often compensated for their inability to spell or do fractions better than some of their students.

| "Knowledge gained by compulsion and under the influence of fear, is of little worth and is not apt long to be remembered." |

"Knowledge gained by compulsion and under the influence of fear, is of little worth and is not apt long to be remembered," To make discipline more important than the pursuit of knowledge implies that the child cannot learn anything in an easy, enjoyable manner. Instead, he or she worries what may happen if the pen is held wrong, a word is mispronounced or a line of poetry is forgotten. As a consequence, children under such constant pressure study with tears in their eyes. Learning thus becomes dreadful, meaningless, a painful must. Little wonder why so many young people want to leave school as soon as they can.

Bates feared corporal punishment as a threat to public education and, in turn, to the democratic process. Countries with unstable or nondemocratic governments, he believed, are those with uneducated citizens. And he faulted those governments where monarchs and churches Control education. "Education unrestricted is the first element of national liberty," best summarize his feelings. Following up this conviction with an equally strong dictum, he wrote,"The man who can neither read nor write is not a fit person to exercise the elective franchise."

Like most progressive thinkers of the mid-19th century, however, Bates hardly pondered the eventual extension of the ballot to literate women and racial minorities.

The progress achieved to date in public education, I am sure, pleases most of us, but would Bates be impressed were he alive today? In many ways, the answer is yes. Since he spun his educational philosophy, however, only two dozen or so states have banned corporal punishment. In Pennsylvania, most school districts, have done likewise.

So, despite more than a century of advances in education, psychology, medicine, etc., that tell us about human behavior, we remain as a nation divided on this question.

To be sure, Bates would be up front today supporting global initiatives to end all corporal punishment. Meanwhile, he might cynically ask his fellow Crawford Countians, "Still paddling the students?" How unconscionable.

A Meadville resident, Ilisevich was a professor of history at the former Alliance College in Cambridge Springs, worked for years as librarian for Crawford County Historical Society and has authored several books on local history. He can be contacted at rdi504@zoominternet. net